Seeking immunity

Vaccines are coming--more arrows in the quiver of immunity against COVID-19

Immunity—it’s a word that conjures images of protection, maybe even invulnerability.

I often tell patients that the purpose of the immune system is to tell friend from foe. Biologically, immunity refers to the ability of the body to defend itself against infection and even cancer. The immune system is a complex mechanism that, when functioning appropriately, recognizes the presence of abnormal antigens (proteins) in human tissue. It could be blood, respiratory tissue, gut or any part of the anatomy.

When the immune system is working well, it is protecting against antigens associated with cancer cells or infections. Sometimes the immune system overreacts to normal antigens in the environment that are not threats. We call these allergies. Sometimes, the immune system reacts against normal human tissue. We call these autoimmune diseases—such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Entire textbooks are written and updated about the immune system. I will not try to “boil the ocean” by trying to sum up all of the immune system as it pertains to COVID-19. Much of the popular press references antibodies. The antibody is a protein the immune system creates that recognizes antigens. When antibodies are detected in blood, they may used as a way to detect whether a patient has been recently or more distantly infected with an infection, depending on which antibodies are present. Nice quick primer of antibodies and more courtesy of Raven the Science Maven is here.

Immunization refers to providing antibodies to protect against an infection—or even cancer. Recovering naturally from an illness may confer immunity, by the development of antibodies in response to infection, but is not immunization.

Immunization may be considered either passive, giving antibodies from an external source, or active immunization, having the patient create their own antibodies from a vaccine. Allowing a disease to run rampant through any population is NOT immunization. Immunizations are tested for efficacy and safety, and are approved when they show benefit over placebo.

One of the first treatments suggested for COVID-19 was convalescent plasma (CP). Plasma is blood that has had cells—red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets (platelets are not technically a cell, but a cell remnant)—removed, leaving behind fluid and blood proteins. Amongst those proteins are antibodies. In patients recovering, or convalescing, from an infection, they should be producing antibody proteins against whatever recent infection they survived. High levels of antibodies take a few weeks to develop, but they may persist for months. CP is the plasma from these recovered patients. It is considered a blood product, just as red cell transfusions and platelet transfusions are also considered blood products. CP treatment could be considered passive immunization, but it is not typically considered that way.

In the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, before we had any proven treatments, it was hoped that convalescent plasma could provide protection. For many months, CP was collected from recovering patients, then administered to other patients actively fighting infection. In the US, no large clinical trials were initially developed to show that CP was actually of any benefit compared to placebo. The gold standard of proving that any treatment is of benefit is the randomized controlled trial (RCT), preferably double blinded. In a RCT, the study group is randomly assigned to get the investigational treatment, or a placebo. In a double blinded RCT, neither the patient, nor the treating team knows whether the patient is getting treatment or placebo.

Instead of an RCT, the initial collection and distribution of CP was done in an uncontrolled way. There was no standardization of CP. There was no placebo group. Now those studies are finally being done, and it appears there may no benefit to CP.

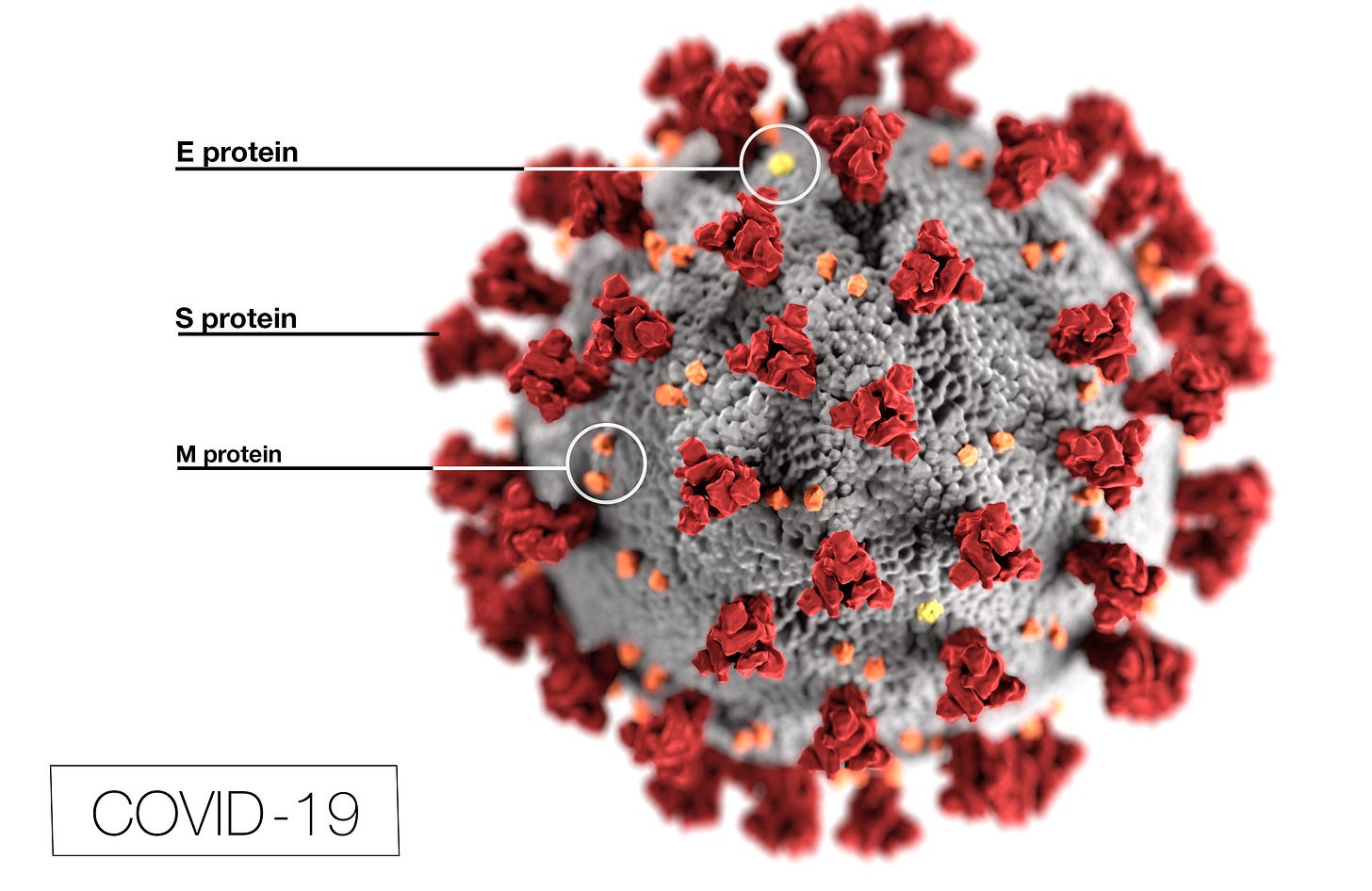

The next form of passive immunization to be tried is monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). mAbs are antibodies designed and produced in a laboratory. They can be designed to recognize any antigen, including from infectious agents or cancer cells. For SARS-CoV-2, the products produced by Regeneron and Lilly are directed at an antigen on the virus called a spike protein (or S protein). While CP may contain antibodies against all sorts of antigens, the mAbs are directed at specific antigens.

Image from cdc.gov

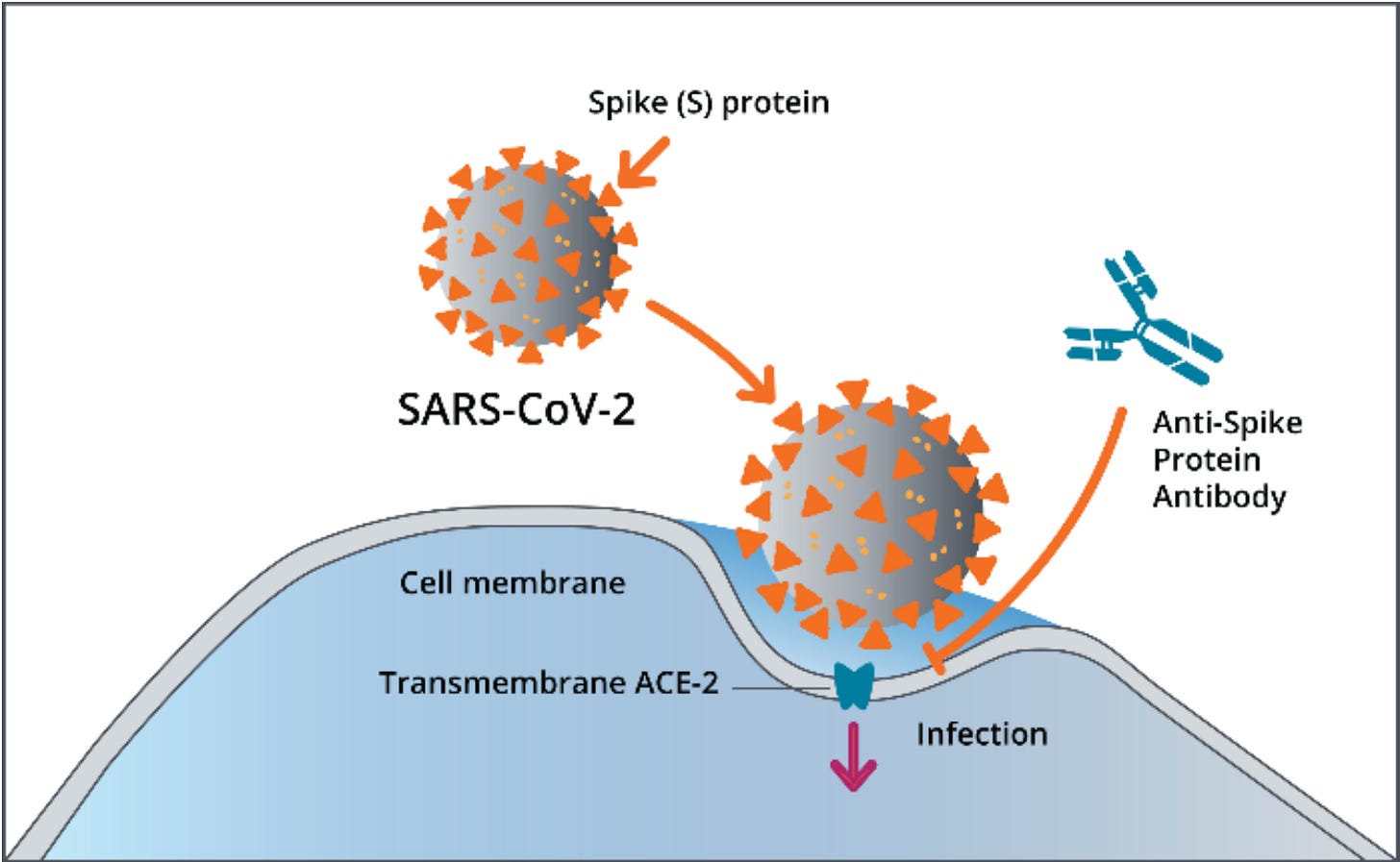

The spike protein is the part of the virus that attaches to human cells. Antibodies against spike proteins may prevent the spike protein of the virus from attaching to the cell, preventing infection.

Image from cdc.gov

The major limitation of passive immunization, whether from CP or mAbs, is that the antibodies don’t last forever. Generally, IgG antibodies—the longest lasting antibodies—have a half-life of 10 to 21 days. This means that in a few weeks, half the antibodies will be gone. For some of these monoclonal antibodies, the half-life may be shorter.

A much more durable form of immunity is active immunization. Teaching the body to make its own antibodies—through vaccination.

Let’s look at that—next!

Excellent explanation of a complex subject. I’ve been reading and hearing about immune therapy for cancer for a few years now, and it’s a difficult topic for a liberal arts grad to grasp. This helps!