Own goal

Why it has been hard for me to write about the measles outbreak

“Do you believe in the vaccines?”

This question was put to me last summer by the CEO of a prominent family-owned local company with global reach. And it made me mad. An obviously intelligent and successful man, he asked a question steeped in suspicion and ignorance. He was referring to the COVID-19 vaccines, but he could have been asking about any vaccines.

When I examine why I have struggled to write a post about the measles outbreak occurring now in Texas and New Mexico— one of the largest single outbreaks in decades, and the first deaths in ten years—the feeling that comes to me is anger. It is not comfortable.

I try to write these entries in a neutral tone. Infections are part of our natural world. Sometimes they are unpredictable; sometimes they are unavoidable. I may get dismayed about unfortunate decisions people make, but that is part of the human condition. So anger is not something that is typically part of my work experience.

Except for one thing: vaccine-preventable infections, especially in children. That makes me angry.

The last time I felt this angry was in late 2021 and into 2022, when almost everyone I saw die from COVID-19 were people who chose not to take a free and then abundantly available vaccine. They had their reasons: don’t trust the science, don’t have time, worried about side effects, it won’t happen to me, the Almighty will protect me. I have heard many excuses. It was almost always adults who died in our hospitals, and they owned their decisions. I was still angry though, because these folks who died didn’t need to. They didn’t need to inflict the pain of loss from premature death on their loved ones.

When kids are involved, though, that feels different, and even more cruel.

I trained in both pediatrics and adult medicine. Ask any pediatrician, and they will tell you that kids are easy to care for. It’s the parents that are difficult. Some are outright abusive, but that is fortunately rare. More often, it is that parents make poor choices for their children. And the worst choice of all, from the perspective of many health care providers, is to not vaccinate them against deadly illnesses.

It is an own goal. It is a loss that could have been prevented.

We had a large outbreak of measles where I live in 2017. Fortunately, there were no fatalities, but there certainly could have been. In all, there were 75 cases, only a quarter of what has been reported so far in New Mexico and Texas. However, it occurred in a urban location, among a population that was undervaccinated. They had been told that measles vaccination increased the risk of autism. Not true, but misinformation has a way of persisting if it is repeated and not countered.

What make measles difficult to contain is that it is incredibly infectious. The infectious virus can persist in the air and on surfaces for hours, even after the ill person has left. Way more infectious than COVID-19, influenza, RSV or most of the other common respiratory illnesses. When 9 out of 10 exposed and non-immune people can catch and transmit the disease to others, a high rate of vaccination in the community is the only way to break chains of transmission. This is called herd immunity, and to break the chain, greater than 95 percent of people need to be vaccinated or immune.

The good news is that there is an incredibly effective vaccine against measles—MMR. In people with a normal immune system, a single shot is 93% effective; 97% effective when a second dose is given.

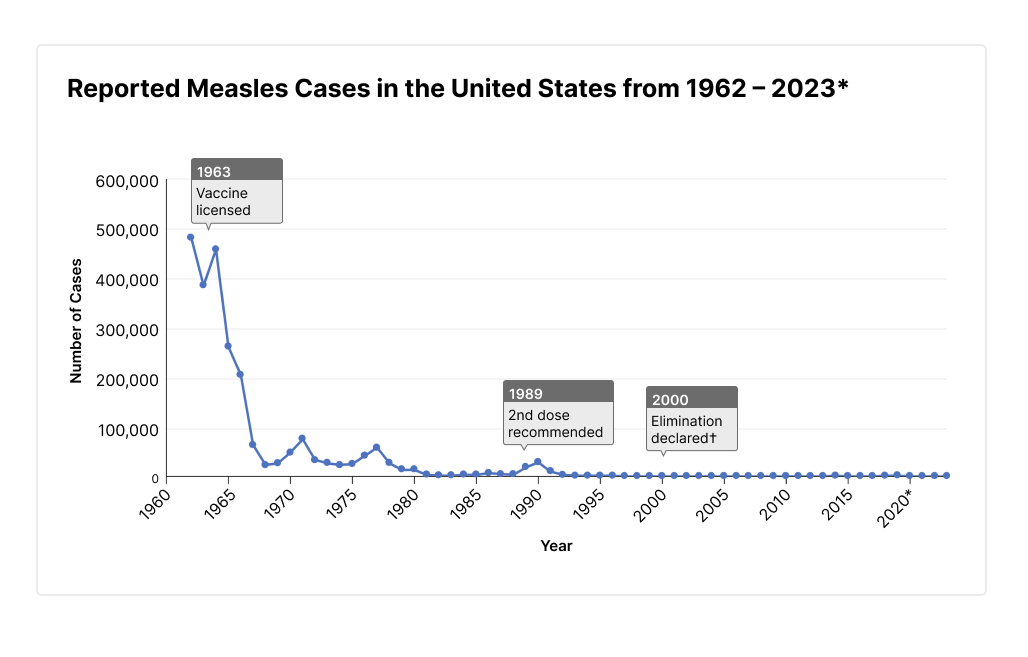

Two dose vaccination essentially eliminated measles transmission in the United States. USA outbreaks now are related to imported cases coming into communities that have low vaccination rates. However, cases are still common overseas, especially in developing countries.

Complications of measles include hospitalization, pneumonia, encephalitis (brain inflammation) and death. A rare complication can occur many years later call subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). A slow death over 1 to 3 years is the common outcome of SSPE.

There is no antiviral medication effective against measles, so the only treatment once an infection has occurred is supportive care. Vitamin A is only effective at reducing some side effects in very malnourished children. Even then, there is risk of permanent injury despite vitamin A administration. Moreover, vitamin A itself is potentially toxic when administered in high doses.

What can you do? First, make sure that you are immune, either from having had the infection (more common in people born before 1957), or by having had TWO doses of vaccine. Especially important if one is traveling to an area where there is still measles transmission.

A doctor can order a blood test to check level of antibody against measles. However, if it is known that two doses of vaccine have been given, then there is little benefit to checking a blood test.

What about if someone is definitely exposed to measles? There is postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) vaccination that can be given within very short time window—an MMR vaccine within 72 hours of exposure, or immunoglobulin within 6 days of exposure. After that, there is no proven medication to prevent illness.

No medication or vaccination has a zero percent harm rate. That includes the MMR vaccine. But the risk of harm from measles or other vaccine-preventable illnesses are so high, that vaccination is the best way to go—for yourself, your children, and the community.

Please don’t make me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.

A clear post that informs individuals, communities, and policy makers.

Excellent writing…terrible that so many don’t prescribe to the social construct of community living. I fear the measles will blow up quickly. Keep sharing.